“Where is the systematic evidence review?”

Although trials of the CBR model in the field have yielded positive feedback from researchers and the community, and the volume of research being published on the topic is increasing, a systematic and balanced body of evidence for CBR is still missing. A meta-analysis of all research is almost impossible given the diversity of methods used among CBR researchers (Wirz & Thomas, 2002).

Conducting primary research is also problematic. Most research papers available are theoretical or descriptive, and much of the knowledge is incapable of being generalized across regions and cultures (Wirz & Thomas, 2002; Finkenflügel, Wolffers, & Huijsman, 2005). Quantitative study models are not often compatible with CBR due to logistical issues such as lack of baseline data, lack of statistical expertise among CBR workers, and ethical issues with randomization in cross-cultural settings (Sharma, 2004). For example, the costs of running a CBR program may be divided among several administrative levels and may overlap with those of other services, including institutional care; this makes it difficult to compare the relative cost-effectiveness of CBR against that of institutional rehabilitation (Finkenflügel, 2004). Conversely qualitative researchers may feel resistance against using quantitative study models to describe the benefits of a social model approach to disability (Velema, Ebenso, & Fuzikawa, 2008). There is also the issue of limited research capacity and the low prioritization of research activities in certain low-resource environments (Finkenflügel, 2004).

As a result of these challenges the continued relevance of the CBR model has been called into question (Finkenflügel, 2009).

Conducting primary research is also problematic. Most research papers available are theoretical or descriptive, and much of the knowledge is incapable of being generalized across regions and cultures (Wirz & Thomas, 2002; Finkenflügel, Wolffers, & Huijsman, 2005). Quantitative study models are not often compatible with CBR due to logistical issues such as lack of baseline data, lack of statistical expertise among CBR workers, and ethical issues with randomization in cross-cultural settings (Sharma, 2004). For example, the costs of running a CBR program may be divided among several administrative levels and may overlap with those of other services, including institutional care; this makes it difficult to compare the relative cost-effectiveness of CBR against that of institutional rehabilitation (Finkenflügel, 2004). Conversely qualitative researchers may feel resistance against using quantitative study models to describe the benefits of a social model approach to disability (Velema, Ebenso, & Fuzikawa, 2008). There is also the issue of limited research capacity and the low prioritization of research activities in certain low-resource environments (Finkenflügel, 2004).

As a result of these challenges the continued relevance of the CBR model has been called into question (Finkenflügel, 2009).

Solution 1: Find new and innovative ways of conducting and synthesizing CBR research.

It has been suggested that a quantitative view of CBR is inappropriate for measuring the outcomes of this holistic and dynamic form of care, and that qualitative studies may better reflect the subjective nature of community and individual experiences of disability (Cheausuwantavee, 2007). Indeed Finkenflügel (2004) warns against attempting to structure a CBR program as a quantitative experiment as this makes it less flexible to respond to the needs of the actual clients of the program.

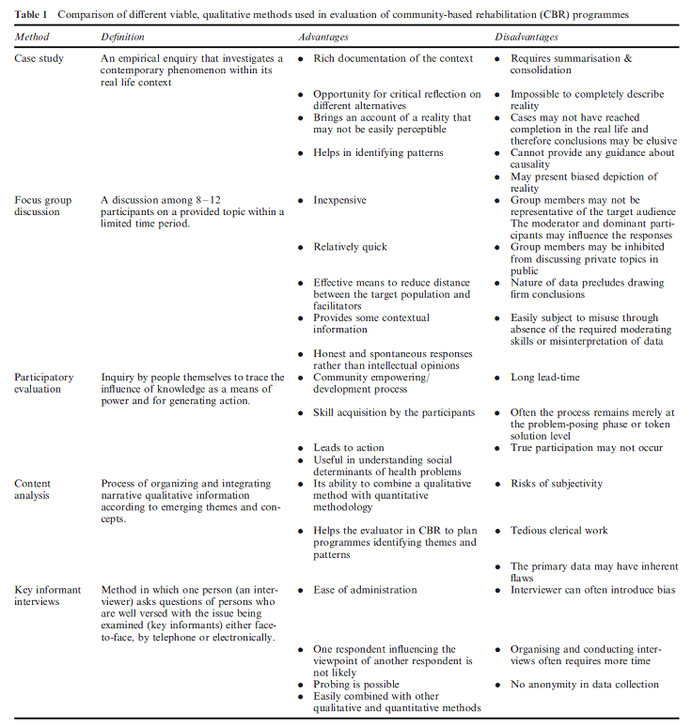

Recently Sharma (2004) reviewed a series of qualitative study types that are currently used for CBR projects. Each study type poses various advantages and disadvantages:

Recently Sharma (2004) reviewed a series of qualitative study types that are currently used for CBR projects. Each study type poses various advantages and disadvantages:

(Sharma, 2004)

Sharma notes that qualitative studies are effective for developing hypotheses but are less generalizable, precise, and controlled than quantitative studies. Thus, mixed methods studies for evaluating CBR programs should be used where possible (Sharma, 2004).

In addition to examining the merits of qualitative versus quantitative study types, many researchers have proposed specific indicators for monitoring the success of CBR programs. The challenge lies in field testing these suggested indicators, ideally across various environments (Wirz & Thomas, 2002). Some researchers have also developed flow charts and other devices so that program evaluators can more easily evaluate large quantities of indicators (eg. Cornielje, Nicholls, & Velema, 2000; Velema & Cornielje, 2003; Finkenflügel et al., 2008).

Based on UN guidelines, indicators for CBR should be agreeable to all stakeholders (including persons with disabilities and their communities), measured through standard scientific criteria, and few in number (Wirz & Thomas, 2002). In reviewing indicators used for 10 different CBR projects, Wirz & Thomas (2002) also recommended that indicators be applicable to specific locales and program objectives and be easy for field workers to use.

Although evidence of the efficacy of CBR programs is needed in many areas, particular areas that require attention in research include community participation and use of local resources (Finkenflügel et al., 2005). Mitchell (1999) outlines 4 priority research areas for CBR: service delivery system, technology transfer, community involvement, and organization and management. He notes that this is not an exhaustive list and that other considerations such as cost-effectiveness and the involvement of rehabilitation specialists are also key.

In addition to examining the merits of qualitative versus quantitative study types, many researchers have proposed specific indicators for monitoring the success of CBR programs. The challenge lies in field testing these suggested indicators, ideally across various environments (Wirz & Thomas, 2002). Some researchers have also developed flow charts and other devices so that program evaluators can more easily evaluate large quantities of indicators (eg. Cornielje, Nicholls, & Velema, 2000; Velema & Cornielje, 2003; Finkenflügel et al., 2008).

Based on UN guidelines, indicators for CBR should be agreeable to all stakeholders (including persons with disabilities and their communities), measured through standard scientific criteria, and few in number (Wirz & Thomas, 2002). In reviewing indicators used for 10 different CBR projects, Wirz & Thomas (2002) also recommended that indicators be applicable to specific locales and program objectives and be easy for field workers to use.

Although evidence of the efficacy of CBR programs is needed in many areas, particular areas that require attention in research include community participation and use of local resources (Finkenflügel et al., 2005). Mitchell (1999) outlines 4 priority research areas for CBR: service delivery system, technology transfer, community involvement, and organization and management. He notes that this is not an exhaustive list and that other considerations such as cost-effectiveness and the involvement of rehabilitation specialists are also key.

Solution 2: Build monitoring and surveillance into the program from the outset.

Velema, Finkenflügel and Cornielje (2008) suggest that maintaining an information system for CBR clients from the outset will enable retrospective cohort studies to be conducted at a future point, lending credence to the CBR model. Turmusani, Vreede, and Wirz (2002) further suggest that persons with disabilities can contribute to monitoring CBR programs given their expertise as users and as persons with lived experience; such an exercise can elevate the profile of persons with disabilities in CBR-related activities. General activities for health systems strengthening to heighten the research capacity in developing countries are also recommended (Finkenflügel, 2004).

References:

Cheausuwantavee, T. (2007). Beyond community based rehabilitation: Consciousness and meaning. Asia Pacific Disability Rehabilitation Journal, 18(1), 101-109.

Cornielje, H., Nicholls, P. G., & Velema, J. (2000). Making sense of rehabilitation projects: Classification by objectives. Leprosy Review, 71(4), 472-485.

Finkenflugel, H. (2004). Empowered to differ – Stakeholders’ influences in community-based rehabilitation. Amsterdam: Vrije Universiteit.

Finkenflügel, H., Cornielje, H., & Velema, J. (2008). The use of classification models in the evaluation of CBR programmes. Disability and Rehabilitation, 30(5), 348-354.

Finkenflügel, H., Wolffers, I., & Huijsman, R. (2005). The evidence base for community-based rehabilitation: A literature review. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research, 28(3), 187-201.

Mitchell, R. (1999). Community-based rehabilitation: The generalized model. Disability and Rehabilitation, 21(10-11), 522-528.

Sharma, M. (2004). Viable methods for evaluation of community-based rehabilitation programs. Disability and Rehabilitation, 26(6), 326-334.

Turmusani, M., Vreede, A., & Wirz, S. L. (2002). Some ethical issues in community-based rehabilitation initiatives in developing countries. Disability & Rehabilitation, 24(10), 558-564.

Velema, J. P., & Cornielje, H. (2003). Reflect before you act: Providing structure to the evaluation of rehabilitation programmes. Disability and Rehabilitation, 25(22), 1252-1264.

Velema, J. P., Ebenso, B., & Fuzikawa, P. L. (2008). Evidence for the effectiveness of rehabilitation-in-the-community programmes. Leprosy Review, 79(1), 65-82.

Velema, J. P., Finkenflügel, H., & Cornielje, H. (2008). Gains and losses of structured information collection in the evaluation of ‘rehabilitation-in-the-community’ programmes: Ten lessons learnt during actual evaluations. Disability and Rehabilitation, 30(5), 396-404.

Wirz, S., & Thomas, M. (2002). Evaluation of community-based rehabilitation programmes: A search for appropriate indicators. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research, 25(3), 163-171.

Cheausuwantavee, T. (2007). Beyond community based rehabilitation: Consciousness and meaning. Asia Pacific Disability Rehabilitation Journal, 18(1), 101-109.

Cornielje, H., Nicholls, P. G., & Velema, J. (2000). Making sense of rehabilitation projects: Classification by objectives. Leprosy Review, 71(4), 472-485.

Finkenflugel, H. (2004). Empowered to differ – Stakeholders’ influences in community-based rehabilitation. Amsterdam: Vrije Universiteit.

Finkenflügel, H., Cornielje, H., & Velema, J. (2008). The use of classification models in the evaluation of CBR programmes. Disability and Rehabilitation, 30(5), 348-354.

Finkenflügel, H., Wolffers, I., & Huijsman, R. (2005). The evidence base for community-based rehabilitation: A literature review. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research, 28(3), 187-201.

Mitchell, R. (1999). Community-based rehabilitation: The generalized model. Disability and Rehabilitation, 21(10-11), 522-528.

Sharma, M. (2004). Viable methods for evaluation of community-based rehabilitation programs. Disability and Rehabilitation, 26(6), 326-334.

Turmusani, M., Vreede, A., & Wirz, S. L. (2002). Some ethical issues in community-based rehabilitation initiatives in developing countries. Disability & Rehabilitation, 24(10), 558-564.

Velema, J. P., & Cornielje, H. (2003). Reflect before you act: Providing structure to the evaluation of rehabilitation programmes. Disability and Rehabilitation, 25(22), 1252-1264.

Velema, J. P., Ebenso, B., & Fuzikawa, P. L. (2008). Evidence for the effectiveness of rehabilitation-in-the-community programmes. Leprosy Review, 79(1), 65-82.

Velema, J. P., Finkenflügel, H., & Cornielje, H. (2008). Gains and losses of structured information collection in the evaluation of ‘rehabilitation-in-the-community’ programmes: Ten lessons learnt during actual evaluations. Disability and Rehabilitation, 30(5), 396-404.

Wirz, S., & Thomas, M. (2002). Evaluation of community-based rehabilitation programmes: A search for appropriate indicators. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research, 25(3), 163-171.